Personalized AI advisors and AI agents are rapidly becoming a reality for consumers. These AI systems have the potential to make the marketplace more convenient and efficient – but they also could bring about new threats, especially if consumers lose a sense of choice and control.

That’s why in the summer of 2025, I joined the Innovation Lab at Consumer Reports (CR) as a Siegel Family Endowment PiTech PhD Impact Fellow, focusing my research on how we might design AI systems that give consumers real agency and the ability to personalize their experiences.

The Current AI Landscape

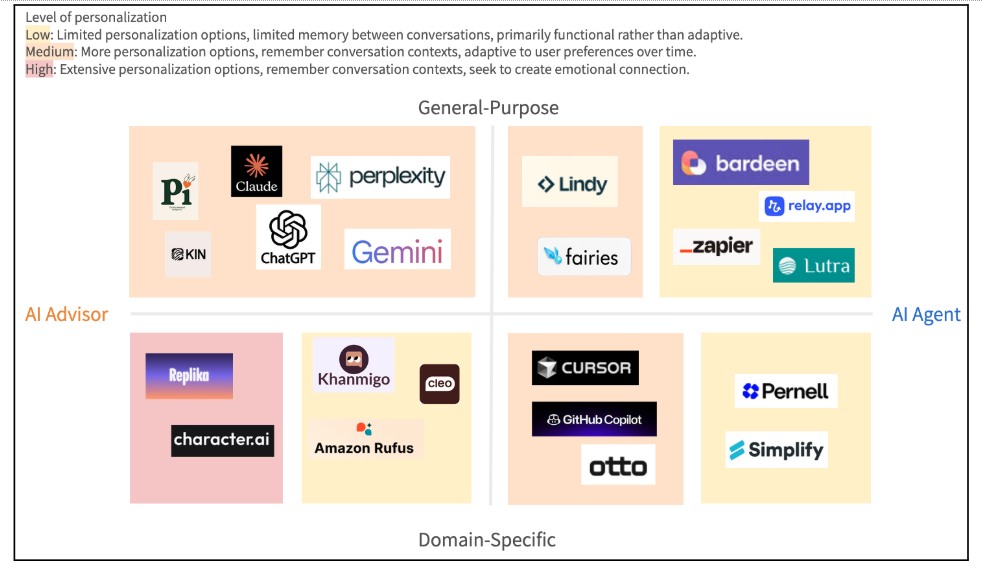

I started my research by conducting a landscape analysis of 11 AI consumer facing advisors and 11 AI agents. I drew the distinction between the two based on their primary mode of interaction: AI advisors primarily engage users through conversations, whereas AI agents are oriented toward executing tasks on users’ behalf. For each system, I examined its homepage to see how it presented to users. Then I interacted with it as a user, starting with signing up then proceeding to have conversations and create tasks, depending on the system’s capabilities. I also explored the app’s privacy settings and personalization features.

I mapped out each system’s level of personalization based on available personalization options in settings, memories between conversations, and the ability to adapt to user preferences over time. I also documented the user interface designs these systems use to request user consent for using personal data and for making decisions on users’ behalf.

Takeaways

Overall, I found that AI advisors have a higher level of personalization than AI agents. Similarly, general-purpose AI systems offer a more personalized experience than domain-specific ones, with the exception of AI companions specifically designed to foster long-term social relationships with users.

Figure 1. The landscape of 22 AI systems, categorized by interaction type and scope.

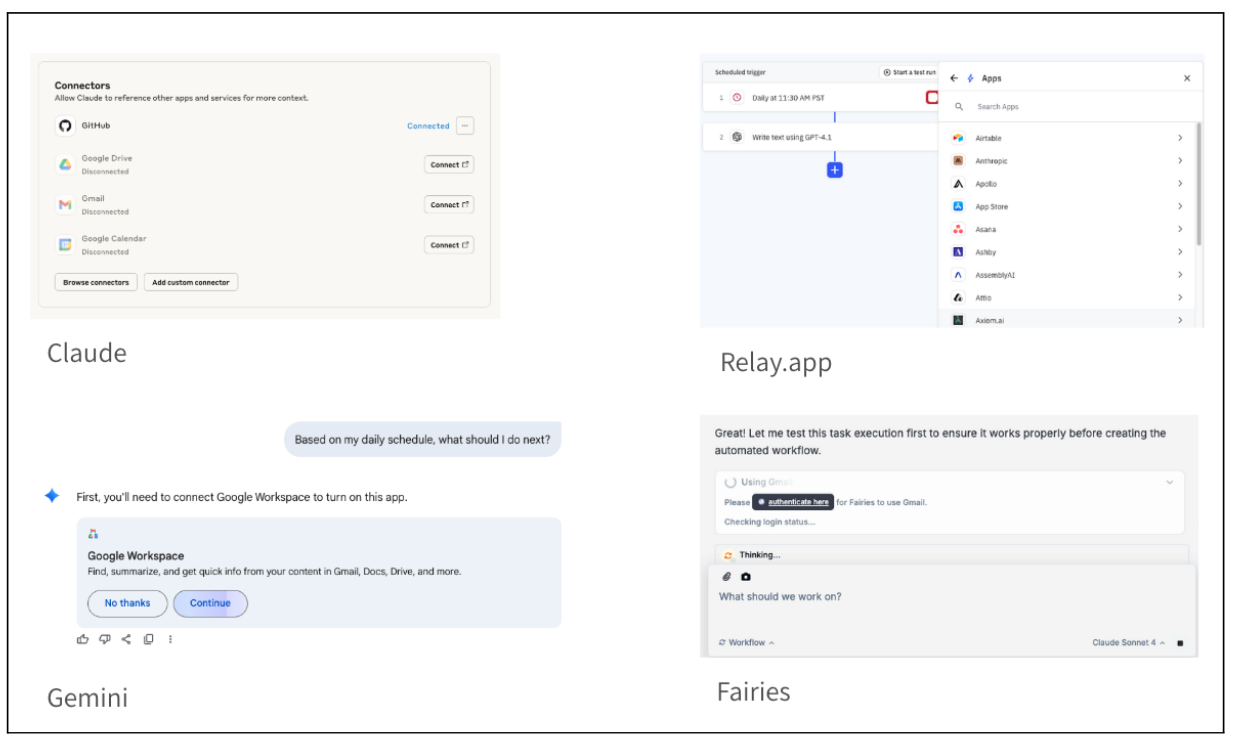

The AI systems I surveyed draw on a wide range of data sources – including chat memory, manual user configurations, and integrations with external services – to personalize user experiences. I found a variety of different consent and personalization practices, but overall, there lacks a consistent standard across systems. This inconsistency highlights how unsettled the design space remains for consumer-facing personalized AI systems. While frameworks such as Human Context Protocol (HCP) offer a promising path toward greater consistency and portability between systems, they have yet to be widely adopted.

Figure 2. Examples of different ways AI systems request permissions to connect with external services.

Hearing from Consumers

CR has its own AI advisor, AskCR, which answers questions based on CR’s trusted data and research. As we think about how AskCR might evolve, we need to take a step back and ask: how do consumers perceive these consent and personalization practices used in today’s AI systems?

To answer this question, I conducted semi-structured interviews with 10 participants who had used AI in their shopping journey. Here, I narrowed down the context of use to shopping to get more targeted insights that we can apply to AskCR in the future.

In the interviews, I started by asking consumers about their recent AI shopping experiences, successes, and challenges, and then their desired features for next-generation shopping AI. I then dove deeper into their attitudes and expectations regarding consent and personalization in AI advisors and agents.

Personalization over Privacy: “Know Me Very Well… But Not Too Well”

First, I found that consumers are excited about personalized AI shopping systems and are generally open to sharing substantial personal, even sensitive data, in exchange for personalized experiences. Many perceive that the benefits of personalization outweigh the cost of privacy. For example, one participant kept personal information in AI memories despite privacy concerns because generic responses would be “not useful anymore.” In addition, some participants also feel their data is already compromised by data brokers, so sharing with AI doesn’t make things worse. However, when prompted to reflect on potential data misuse, participants’ attitudes became more cautious. Several drew lines around financial and health information, while others acknowledged that they “hadn’t really thought about it before”. Some also raised concerns about scenarios where AI agents might make mistakes using their personal data.

Information Overload: “Make it Easy for Me”

Second, I found that consumers are too decision-fatigued to configure AI tools. As one participant put it: “I am challenged sometimes when I’m given so many options.”. They all choose AI tools that are already part of their existing routines and device ecosystem for their shopping research, and rarely adjust default data-sharing or personalization settings. They also prefer having AI systems learn their preferences automatically through conversations and interactions – “almost like if you have someone following you around and taking notes on what you do” and are willing to connect the AI tools to their shopping sites to access their purchase history for better personalized experiences. In contrast, they show less interest in setting up their preferences in AI tools manually. As one participant said: “I am not manually putting down anything”.

Trust is Essential: “Prove I Can Trust You, Before Taking Control”

Lastly, I saw a big difference in consumers’ mental models for AI advisors vs. AI agents. On the one hand, participants described personalized AI advisors as if they were their friends. Trust is established through first impressions – including positive anecdotes from others, and a clear guarantee that the AI will not sell or share their information. While comfortable sharing personal information, they want clear boundaries – they don’t want AI advisors to dwell on what they perceive as sensitive topics or make sensitive inferences, and find it creepy when AI remembers things they’ve forgotten.

On the other hand, participants described personalized AI agents as if they were novice assistants. They do not trust AI agents’ capabilities yet and therefore would only delegate routine, low-stakes tasks with no emotional or interpersonal sensitivity to AI agents. They want tight control with constant human approval of AI agents’ actions via push notifications. Importantly, participants’ definition of what’s considered sensitive information, or high-stakes tasks, is dynamic and contextual – for example, one participant mentioned not wanting AI to obtain medical information – unless she is asking for suggestions about supplements.

Designing for Consumer-First AI

The landscape analysis and user research helped me develop high-level design principles for AI systems that give consumers real agency and the ability to personalize their experience. The 3 core design principles are:

- Transparency. Users should always understand what the AI knows about them and how it uses that information.

- Contextual Consent. Rather than asking for broad permissions upfront, consent should be collected when and where it becomes relevant and useful to the user.

- User in Control. Users should remain the primary decision makers, with the AI system serving their choices rather than making choices for them.

Prototyping the Future of AskCR

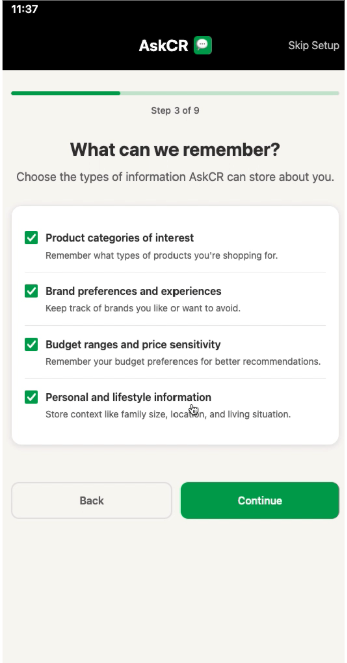

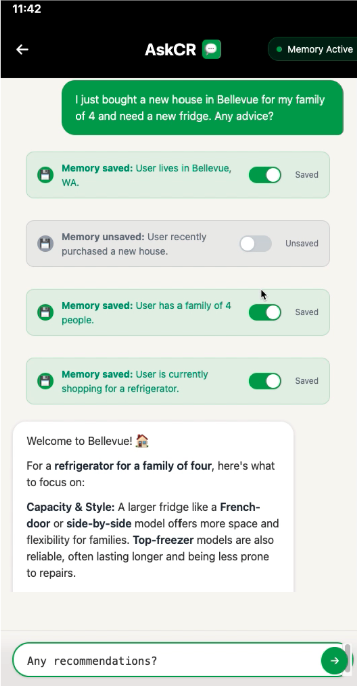

Guided by these high-level design principles and concrete patterns identified in my earlier research, I created mid-fidelity interactive prototypes to illustrate how these principles could play out in a future version of AskCR.

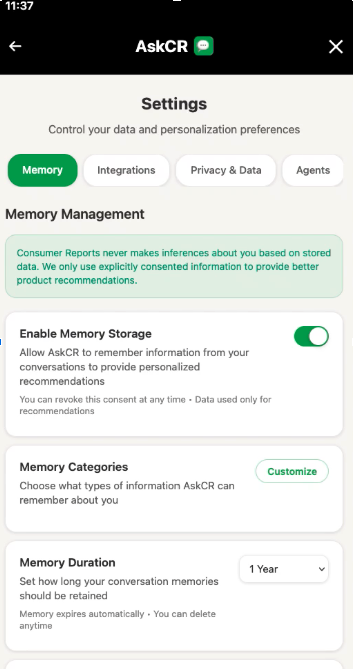

Figure 3. Exploratory mid-fidelity prototypes for onboarding, conversation, settings, and agent dashboard interfaces. Not a live version of AskCR.

Onboarding. The prototype begins with a structured setup flow that introduces trust from the start. Each step explains – in plain terms – what data is collected and why, while letting users exercise target consent (e.g., sharing purchase history for some product categories but not others).

Conversations. To surface moments of consent in ongoing conversations, I designed a “memory indicator” that signals when user information is stored or recalled by the systems, and allows users to opt out in real time. I also explored how AI agent functionalities might be integrated into conversations.

Settings. Users can view and manage how AskCR engages with their data, from memory controls to privacy preferences. Each section includes a clear ethical code, paired with granular controls at multiple levels.

Agent dashboard. As a forward-looking addition, I designed a dashboard where users could directly view and manage specialized agents’ actions. An activity log provides visibility of agents’ actions. Users can also decide which actions agents may take automatically and which require explicit approval.

Next Steps

My work has provided the initial insights on how a personalized shopping AI system might engage with consumers. Moving forward, more work will be needed to translate these design concepts into production-grade experiences.

Additionally, my findings show that many consumers are willing to trade privacy and control for convenience in AI personalization. While this observation may seem in tension with consumer protection goals, a closer look reveals that such attitudes often stem from consumers’ perception that the benefits of personalization are immediate and tangible, whereas the risks of data misuse or privacy breaches feel abstract and distant. Addressing this tension requires a twofold approach. First, AI systems should be designed to carefully balance consumers’ desire for convenience with meaningful safeguards that preserve their privacy and agency. Second, we need stronger digital literacy initiatives that help consumers recognize – and more accurately weigh – the long-term implications of data sharing.

Joining CR as a Fellow this summer, and working on this project has been such a valuable experience. It wasn’t just about tackling technical and design challenges – it also got me thinking more about the values people bring into their interactions with AI. One idea that stuck with me is how we think about “consent” in digital technology: not as a fixed formality, but as an evolving process that must adapt as both technology and people’s understanding of technology evolves. I’d love to keep the conversation going with anyone thinking about these questions, so please feel free to reach out at yw2547@cornell.edu.

Special thanks to Dan Leininger, Daniella Raposo, Ginny Fahs, Melissa Garber, Juan Ricafort, Justin Huynh, and Cody Juric at Consumer Reports, and Deborah Estrin, Kate Nicholson, Malgosia Rejniak, and Joanna Delgado from the Cornell PiTech team for their support and guidance throughout this Fellowship.