In the midst of a historic election, a global pandemic, and a social justice movement against systemic racism against black people, researchers and practitioners continue to address: Who sets the agenda for research? How is it executed? Who benefits from that research?

To bring more light to these questions, Consumer Reports, Rita Allen Foundation and Citizens and Technology Lab at Cornell recently organized a panel discussion about citizen science — the practice of public participation and collaboration in research to increase knowledge, improve outcomes and reduce harms. We discussed the challenges and opportunities in research powered by the immersion, understanding and participation of the communities around us.

Our goal was to explore how organizations can improve how we work with diverse communities and organizations. How can we better identify shared issues of harms and discourse as it relates to the internet, our environment or our bodies? Reducing online harassment for women, testing water contamination in communities, or creating safeguards to contribute genetic data for research requires a genuine connection and understanding for those who this work impacts.

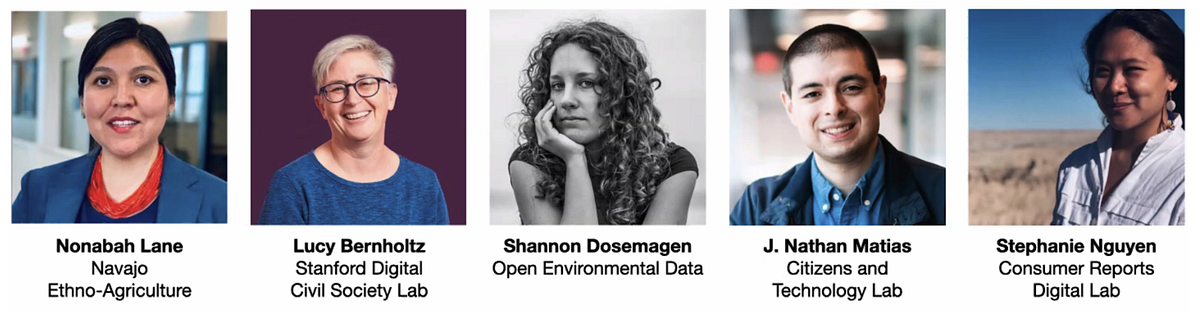

For decades, researchers, technologists and practitioners have created relevant participatory design principles, frameworks for design justice and deliberate design, and employed countless public participation models to shift power in decision making. Research drives the products and services we use, the policies and laws that govern our communities, and the societal norms and habits that drive our culture. The hope for this conversation was to highlight how our invited panelists are thinking through public engagement and participatory research methods in practice. The panelists include:

- Lucy Bernholz @p2173 @DigCivSoc: Director, Digital Civil Society Lab, Stanford University

- Shannon Dosemagen @sdosemagen @OpenEnviroData: Director and Civic Science Fellow, Open Environmental Data Project

- Nonabah Lane Navajo Nation, Director at Navajo Power-New Mexico, Cofounder of Navajo Ethno-Agriculture

- J. Nathan Matias @natematias @Cornell: Founder, Citizens and Technology Lab, Cornell University

- Stephanie Nguyen @stephtngu @ConsumerReports: Researcher at Consumer Reports, Rita Allen Civic Science Fellow, moderator

In the first half of the event, panelists did quick lightning talks that explored: What communities are you serving and what problems do they need to solve? How do communities get involved? How do you and communities understand impact?

After acidic mining waste contaminated rivers and irrigation systems in their community in New Mexico, Navajo Nation member Nonabah Lane launched a campaign to partner with local Navajo schools and tribal colleges to create their own water testing capabilities and translate that data into information to local farmers. To date, her team aims to develop user-friendly tools that are low cost so that it is accessible to underserved farmers and agriculturalists in tribal communities.

People are using apps like ebird, iNaturalist or are participating in patient trials to measure aspects of their own physical or emotional states toward a single massive dataset. “[We’re] trying to understand what people think they’re doing when they participate [whether it is] contributing to something philanthropically or building a bigger data set,” Lucy Bernholz explains. “We need to think hard about what philanthropy is and what kind of behaviors count, what it means to volunteer, and who has real access [and gets privileged] to these systems?”

Shannon Dosemagen, recently began the Open Environmental Data Project to create space for people to collaborate and solve environmental challenges and issues. “When I started with my previous organization, Public Lab, a decade ago during the BP oil disaster, we weren’t getting good information from federal agents and contractors,” she explained. “We came together to create our own imagery and documentation using an open hardware tool.” Dosemagen focuses on how to translate data from communities to policymaking, and creating governance systems for environmental data and information.

Witnessing severe harassment, threats and attacks on women through online platforms, Nathan Matias worked with Women Action & the Media to identify areas where Twitter fell short to get law enforcement help, bring attention to lawmakers, and make advances in understanding human behavior and social interaction. Through randomized controlled trials, Matias also organized with hundreds of Wikipedians to send messages of appreciation to contributors. A “thanks” message increased participation on Wikipedia and caused people to pass it on.

In the second half of the panel, we dove into more specific questions into the work regarding each of the panelists.

SN: How has your work and roles shifted around the pandemic to more directly address and solve issues around public health in Navajo Nation?

NL: We’ve shifted how we run an education farm and now shifted more toward serving the community more as a charity. I am involved in a higher policy level at the federal level to include tribal communities in structuring the growth of the economy. I am working on a couple of projects that address public health by getting personal protective equipment (PPE) to tribal communities. Hopefully we can get into actual manufacturing and distribution of these things directly. It’s time for change.

SN: Who determines what is credible, especially in the work that you mentioned looking at online harassment with Twitter. Since science or the lack thereof is highly politicized, how do you protect from false information?

NM: The assumption is that if you work with communities, you’re not working with experts and the quality of your work goes down. When you actually talk to people who understand the context deeply and face the issues you’re working on, you discover all sorts of things as a scientist you would never have thought of and that pushes the quality of the work. So that’s where a partnership with communities is incredibly valuable because we can bring the rigor of knowing about statistics in social research and building work that can get peer-reviewed and have that layer of credibility. Communities can also bring their deep expertise and knowledge to the process to ensure the work is meaningful and reliable.

SN: Is it worth it for people to engage in donating data to these data repositories or are things being taken from individuals and communities without any value in exchange? When we think about power and white western privilege and data from marginalized communities, what are the challenges we need to overcome?

LB: At this point in time, civic science offers a potential way to mitigate the typical white western extractive data relationship when there are actual communities and individuals leading the work. What white western institutions need to do is figure out how to get out of the way or how to directly make addressing structural racism fully a part of what they’re trying to do and then engage with those communities. There’s no guarantee that these won’t be extractive relationships, it takes direct intentionality. And frankly, that’s about making the pursuit of the end of structural racism center to the work.

SN: In terms of systems change, you talked a bit about congressional modernization working a system for public witness commentary to serve diverse constituents. How are you thinking about shifting these frameworks in the environmental sector?

SD: The systems we have currently set up to protect and manage the environment are built on having a scarcity of resources. My work started out with: how do we move community data to be more impactful for the priorities and goals? We had to shift the systems that we were working within. [We can look to people like] Elinor Ostrom’s Commons based principles to reimagine an ecological future in which we’re talking about resources as abundant and generative rather than as being scarce. We see how data and information moves to Congress to see who sets the laws that are then going to govern our environmental and health futures. We’re thinking about ways that can get people of a much more diverse Congressional constituency involved in public witness around environmental issues.

SN: There are people who are joining this event who are conducting their own research or hope to contribute to the research you’ve all mentioned. What is one thing people can do next if they’re excited about these issues?

- NM: CAT Lab is collaborating with Consumer Reports to develop some ideas for a new Civic Science project. Please fill out the survey, we’re excited to hear from you.

- LB: Remember that it’s not just your time, it’s not just your money, but it’s also your digital data and your digital behavior. Think about if and how that might be something you want to contribute and what it would take for you to be able to do that in a positive and safe way.

- SD: Even if you have the smallest of ideas that may seem very tiny, to try them out and be willing to put something out into the world to test and ask for feedback and to not have that part of the process be scary. I think many times talking to other people is where we get held up on, so you have to have that willingness to engage. We have a lot of problems to solve and that’s how we’re going to be able to do it.

- NL: It’s important to find and identify those community champions who are in the community, from the community, know all the issues that surround the community and the cultural values. It took me about three years to relearn my own community and to be as impactful as I am now. This is why we formed our own organizations because we were tired of people coming in, not committed and extracting our research, our data, our culture, our language. Let’s form our own farm, our own partnerships and we control everything to influence future generations.

Many thanks to Lucy Bernholz, Shannon Dosemagen, Nonabah Lane, and Nathan Matias for joining us in this discussion and to the many staff members at Rita Allen Foundation and Citizens and Technology Lab for helping to produce this event. As we continue to engage in the work, we must do so first with humility and listen to different sources of knowledge to test these approaches with experiments and then share what we’re learning with the broader community.

Please help us continue the momentum and take our survey. As we plan for future participatory research studies — working with participants like you is key to understanding and illuminating potential harms. We would like to know what topics are of greatest interest.

For a full video recap of the panel discussion, please visit: